Is gut feeling a proxy for experience?

And does gut feeling have a place in a data-driven world?

This week I was reflecting on a blog I read that made me re-think how much weight we put in data when making decisions. I was surfacing for some blogs on experimentation and found a story that could have changed Airbnb’s growth story.

Did you know that Airbnb might have been saved in 2013 because someone didn’t trust the data?

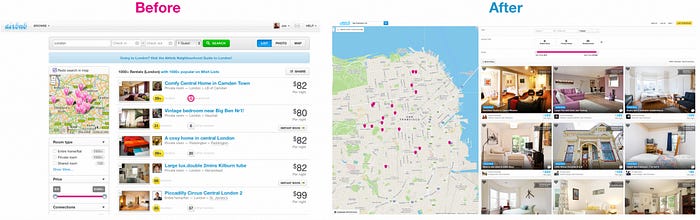

Okay, maybe “saved” is a bit dramatic as the folks at Airbnb are brilliant, and they probably would’ve figured things out eventually. But, this is a real story, one that is even featured in Airbnb’s engineering blog for posterity! Here is the summary of what happened. Airbnb was rolling out a major redesign, testing the new look against the old to see if users preferred it. When the results came back, though, they were disappointing. The data showed no real improvement. Travellers were booking at the same rate as before.

But that didn’t make any sense to the folks at Airbnb. Instead of blindly trusting the data, they dug deep and found that the implementation of the new website had bugs for many users, and therefore, they were not fully experiencing the new design as intended. Once that was discovered and fixed, guess what? Airbnb saw a massive success in how travellers started to use the site.

So what prompted some people in the team to not trust the data? They might have had other data points to build that contextual knowledge to “feel” that something was not right. Or they might have simply had prior experiences to know that this didn’t make sense - for example, someone in the team might have worked for a competitor and knew the massive upsides that existed when bigger pictures and a bigger map was used.

This example is similar to many other discussions I have with my data science team and stakeholders. I have heard many times executives talk about being “data-driven” and following “what the data says”. They talk about data as if it was this omnipotent entity that represents truth. The funny thing is that those who work deep in the data space are the ones who mistrust data the most. And, if we mention mistrust, that means there is something that you can’t initially fully explain that makes you question a “truth” data point. Can that be gut feeling?

The unease of having to balance “gut feelings” with “data-driven” cultures prompted me to read a lot more about decision making. I hope this blog post summarises my learnings in a way that can help you navigate the conundrum between taking decisions with no-data-at-all or going to the extreme of only-what-the-data-says approach.

What we will cover in the blog?

The science behind gut feelings and decision-making — what’s going on in our brains when we make snap judgments?

How experience shapes our gut feelings — how are gut feelings formed over time?

When gut feeling is especially valuable — are there situations where we should trust our instincts?

The biases of relying solely on gut feelings — when can gut feelings lead us astray?

Balancing gut feeling with analytical rigour — how can we combine intuition with data for smarter decision-making?

Let’s begin!

The science behind gut feelings and decision-making

Our ancestors had to think really fast to stay alive

Our brains evolved for survival. When early humans faced potential threats, like a predator in the bushes, they had to make split-second decisions, it was about reacting quickly to stay alive. In Behave: The biology of humans at our best and worst", Robert Sapolsky discusses the role of the amygdala. It is our “threat radar” in our brains. It responds to perceived danger before conscious thought can intervene.

This ability to make rapid, instinctual decisions is deeply rooted in our biology and still shapes how we make decisions today. If you are reading this article, I am pretty sure you are not being chased by a lion, so maybe your daily “threats” are triggered when you are facing a complex or unfamiliar situation. In these cases, “gut feeling” is often your brain’s way of rapidly assessing risk based on patterns and past experiences, even if you aren’t consciously aware of it.

Conscious decision making is capped by our brain processing power

The human brain has a limited amount of conscious brainpower, meaning we can only focus on a handful of pieces of information at a time. However, our brains are processing a vast amount of sensory input and experiences all the time, much of it unconsciously.

Neuroscientist David Eagleman, in Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain, highlights how most of our brain’s activity happens beneath our awareness, constantly analysing details and forming judgments without our conscious input. So when you have a “gut feeling” about something, it’s often the result of these unconscious processes distilling all of that hidden data into a simple, instinctual signal. This unconscious work is why gut feelings can sometimes seem like they “just know” the answer, even when we can’t logically explain it right away.

Kahneman’s System 1 and System 2 Thinking

I really like how Daniel Kahneman, distills the decision making process of the brain in 2 levels in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow.

System 1 is “the fast”. It is automatic and largely unconscious. It is the part of the brain that produces gut feelings. System 1 is what kicks in when you’re driving on a familiar road or recognizing a friend’s face in a crowd.

System 2 is “the slow”. It is analytical, and conscious. It is used when we need to think critically, solve new problems, or make complex decisions.

Most of our day-to-day decisions rely on System 1 because it’s efficient and keeps us moving. System 2, on the other hand, requires more mental energy and focus. Kahneman’s research shows that, while System 1 is powerful and efficient, it’s also prone to certain biases and errors because it jumps to conclusions based on patterns it has seen before (we will touch this section later). System 2, meanwhile, can provide a check against those biases but at the cost of speed and effort.

In the context of gut feelings, System 1 is the driving force. When we sense that something isn’t right or that a situation feels “off,” it is System 1 firing based on our accumulated experiences and emotional responses. However, by tapping into System 2, we can consciously evaluate and balance our gut feelings with logical analysis — the ideal approach for data-driven decisions.

How experience shapes our gut feelings

“Mastery requires patience” - James Clear in Atomic Habits.

We have just learnt that our unconscious brain, the one which triggers gut feelings is really fast. It also seems like it is inaccurate from how Kahneman describes that system 2 needs to kick in to make more judgemental decisions. I would really like to emphasise a point: system 1 does not necessarily need to be inaccurate.

As James C. states, in order become a master at something you need patience. He is evoking to the need of repetition. The same happens with the system 1 part of the brain. The more it has experienced something, the more times it has seen the consequences of doing A or B. Therefore, in the future, system 1 will have a great chance of making the right decision, even before system 2 kicks in.

Applying this to a real-life example, imagine that you are an ML engineer. You might be able to recognise early signs of a system bug just by looking at the behaviour of 1 variable. Or even, by looking at 4 charts at the same time but somehow, their trends don’t match how they should be correlated to each other. You might not be able to fix the bug with system 1, but you have definitely triggered a valuable alert just by “gut feeling”.

Intuitive filtering of information overload

The brain stores experiences and catalogues them almost like a library, where similar scenarios are referenced to make decisions. With this accumulated experience, professionals actually sync system 1 and system 2 in their brains. Professionals learn to filter what is relevant and ignore noise. In complex fields, this skill becomes a kind of “data triage,” where the individual’s gut feeling about what is important is rooted in knowing what details matter most.

For example, a seasoned data scientist may be presented with a massive dataset but intuitively knows which variables are likely to be meaningful. Sure, your system 2 is kicking in to distill the problem, but your system 1 might already be telling you where not to focus on first. This selective focus means gut feelings help narrow down information, reducing overwhelm and improving efficiency in environments with an abundance of data.

When gut feeling is especially valuable

Kahneman suggests that our system 1 kicks in 95% of the time. Most of the percentage are for the everyday tasks. However, there are situations that you might not have faced in the past, where decision making is still primary driven by gut feeling.

In crisis situations, relying on gut feelings can be more practical than waiting for a full data analysis. For example, in a cybersecurity breach, immediate response is critical. An experienced analyst might sense something is off before the data even confirms it, perhaps noticing unusual patterns or subtle irregularities. Or the cyber folks might intuitively triage what areas are of higher or lower priority.

In early stage proof of concept products or services, often require quick adjustments and rapid pivots. When initial data is trickling in and doesn’t yet tell a complete story, gut feelings are often necessary to guide quick recalibrations. For example, imagine a product manager tracking the launch of a new app feature. Early user feedback might not be overwhelmingly positive, but a hunch — informed by the manager’s experience with similar launches — tells them to not deviate from path. They believe that early results are just a product of users getting familiar with the new feature, but that engagement will bounce back up.

In meetings, negotiations, or while interpreting stakeholder feedback, there’s often an underlying “read” of the room. Sometimes, gut feelings are invaluable not just with data, but with people. I have been in a data science presentation, where another experienced manager sensed hesitation or confusion among stakeholders. Even without explicit feedback, this gut feeling prompted her to pivot and clarify key points. Recognising these non-verbal cues can help bridge communication gaps, aligning team efforts more effectively.

The biases of relying solely on gut feelings

Experience shapes our system 1 with the main purpose of keeping you alive. In today’s world, keeping you alive is, of course avoiding danger, but also achieving success through personal relationships and work. Both are key for climbing up Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. The issue is that gut feelings tend to get things right at a broader level, but leads to errors, especially when finer, more precise judgments are needed. This is the definition of having biases: your quick instincts react based on your experience.

There are many types of biases, but I would like to pick on 3 as the one’s we normally face on our day to day roles working in the data space.

Confirmation bias. As humans, we tend to favour information that aligns with what we already believe or have seen before. In a data context, this can look like “torturing the data” until it supports a particular hypothesis or goal. This often happens when people subconsciously search for evidence that confirms their intuition rather than challenging it.

Recency bias. Your system 1 knowledge is constantly getting updated. It’s like a Bayesian system, where priors get updated with new knowledge. Recent events tend to get a higher weighting and one needs to consciously evaluate these against longer history of events. For example, I have seen stakeholders who saw a significant drop in transactions and automatically felt nervous about the next quarter, despite other factors indicating a potential win (in this case, we were gaining market share and therefore, would be in a great position when seasonality picked up again). Relying on this gut feeling alone caused the stakeholder to become super reactive to this downturn spike, until we convinced her that we were more than OK despite the decreasing numbers.

Availability bias. It happens when our intuition is overly influenced by information that is most easily remembered. This bias can lead us to assume that the patterns we are most familiar with are also the most important. Say a data scientist recalls a past project where a particular model worked well, so they instinctively gravitate toward it again in a new situation, even though it may not be the best fit. This is often the case when someone repeatedly uses the same analysis method or tool based on past success rather than tailoring their approach to the new data.

Balancing gut feeling with analytical rigour

How can we leverage the best of both system 1 and system 2? There are 3 things that I have been doing throughout the years to help me strengthen the combination of both systems.

1) Feed system 1 with as many experiences as possible

Our intuition improves with exposure to a variety of experiences. The most valuable experiences are the ones you have personally lived through, but, it is impossible to live every possible experience. However, learning is a proxy for learnt experiences. Learning from books, case studies, courses, and observing others’ work can expand your brain’s internal “database.” Each piece of knowledge builds System 1’s pattern-recognition capabilities, so when a similar situation arises in the future, it can be ready to kick in.

2) Fact-check your gut feelings

Unless you validate the decisions you made and the outcomes of those decisions, then biases will keep being embedded in your system 1 thinking. Even the apparently easiest validations should be fact checked. For example, “we made an extra 1 million from this service!”… sure, at the expense of increasing costs by 1 million too.

For even more subtle situations, feedback is the key element for fact-checking. It is especially helpful when it comes from diverse perspectives. Seeking out contrasting thoughts from others can reveal potential blind spots and broaden your consideration, giving system 1 richer data to draw from and making your instincts more reliable over time.

3) Embed counter-hypothesis analysis in your work

For instance, if you have a strong instinct about a hypothesis, ask yourself, “What would I expect to see in the data if I were wrong?” Thinking through alternative explanations, or even designing small experiments that could disprove your hypothesis, gives System 2 the chance to balance out potential biases in System 1.

Building this counter-hypothesis approach into your process trains your brain to look for balanced outcomes, making both your gut feelings and your analytical insights more reliable. This approach brings out the best of both worlds, where gut instincts guide rapid initial decisions, and analytical rigor ensures they’re grounded in reality.

Summary

Is gut feeling a proxy for experience?

Yes.

And does gut feeling have a place in a data-driven world?

Without a doubt.

In this article, we have explored the science behind gut feelings, understanding how our brains evolved to make quick, instinctual decisions, and how we rely on both System 1 and System 2 thinking to navigate everything from routine tasks to complex challenges. We have looked at the ways experience shapes our intuition, the potential biases that come with relying on gut feeling alone, and strategies for balancing instinct with analytical rigour to improve decision-making..

As a final thought, the next time you feel a tickle in your brain (or gut) about something… do 2 things.

First, trust it. You are aware of it, but you might have lived, read or seen something similar in the past. You alert system is telling you something.

Second, if you have time, pause. What do you know about the situation? What don’t you know? Who knows more than I do about this? If X were true, what should we be seeing (or not seeing)? Allow your system 2 to kick in.

Now, I want to hear from you!

When have you trusted your gut over what the data was telling you?

Was it during a product launch, a hiring decision, or maybe interpreting ambiguous user feedback?

Did it turn out to be the right call or a learning moment?

Have you ever sensed something was “off” in an experiment or dashboard before the numbers caught up?

Or maybe you’ve built your own tricks for blending instinct with data — from post-mortems to counter-hypotheses to “does this even pass the sniff test?”

Drop your stories or struggles in the comments — I’d love to hear how you balance intuition and analysis in your decision-making. 👇

Further reading

If you are interested in more content, here is an article capturing all my written blogs!